“Readicide: noun, the systematic killing of the love of reading, often exacerbated by the inane, mind-numbing practices found in schools” (Gallagher, 2009, p.2).

As part of my dissertation, I’m forced to read both widely and deeply for both my theoretical framework and my literature review. It can be a mind-numbing task. I can also be an incredibly exhilarating task, one that causes the neurons in my brain to start firing rapidly, forcing me to grab for a notebook, computer, or other method to harness those thoughts. When the neurons are going at full-blast, I have full sympathy for my true ADD students in my classroom because it does become difficult to focus in on any one idea, text, question, or random musing. As part of my reading, I have picked up Readicide: How schools are killing reading and what you can do about it by Kelly Gallagher. I will admit that I checked this out of the professional collection of my school library sometime in either 2009 or 2010. I’ve had it so long, I’ve lost track. Thankfully, my librarian is a calm and understanding person, or I’d be in big trouble. Today being the first day of our President’s Day weekend break, I planned to work on my dissertation all day. And work I did. I started by picking up Gallagher’s book, and my neurons began firing by the time I was finished with Richard Allington’s foreword.

I find my brain most active when I passionately connect to the theory in the text I’m reading or I passionately oppose the theory of the text I’m reading. If I feel lukewarm about the literature, the brain is lukewarm. I suspect my students probably feel the same way about texts they are assigned. I should probably ask them. By the first pages I’m passionately connected with the text because Allington is someone I usually agree with and the general theory put forth by Gallagher is that as teachers, especially as teachers who are under pressure for their students to perform at a certain level on state tests, we are killing the love of reading for kids. Instead of making them lifelong readers, we’re making them aliterate – people who can read but don’t.

At this point, I paused. While I’m aware this is happening in schools, I’m fortunate not to work in a district that mandates AR (accelerated reader) as an independent reading program or forces us to do skill and kill test prep. I work in a place that values education and good pedagogy. Teachers in my district have the freedom to design units of study that meet both the district’s objectives and the students’ needs. In other words, we’re trusted as professionals to both know what our students need and have the pedagogy to meet the students’ needs. It’s a good place to work.

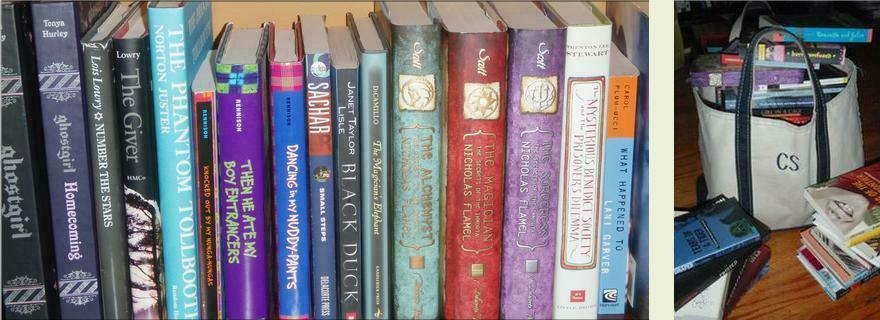

If you’ve read my blog, there’s no doubt that you’ve read about how many books my students are reading or that they come running down the hallway when the Schmidt’s Pick can be checked out so they can be the first to read it or that they don’t start out as readers but become readers over time or they give up social time in order to pass off books to their peers or come visit the class library to check out books. Re-reading these posts, it seems like I teach in some fantasy world. Maybe I do. But the fantasy world extends beyond my room. Speaking with a colleague during a recent PD day, she showed me a blog she’s created with students who have formed a book club with her. Students who are giving up lunch to go to book club.

There’s no secret formula or magic bullet. The secret is giving kids time to read – time free of worksheets and academic expectations. The secret is letting kids have choice in what they read. The secret is reading along with the kids. The secret is recommending books to students and having those books accessible to kids. Gallagher (2009) says that students will not walk the 38 steps to the library to take out a book he’s recommended to them, but if that book is in the classroom, they’ll take it and read it.

Gallagher reaffirmed why I do what I do. Bottom line: time for free choice, independent reading works. Not only does it create a student who reads, it also raises their test scores more than skill and kill worksheets ever could. I found the following statistics somewhat amazing:

Anderson, Wilson and Fielding (1988) reported the following statistics in their study of fifth graders: Those students in the 98th percentile in reading read 90.7 minutes per day and read an estimated 4,733,000 words per year.

Students in the 70th percentile in reading read 21.7 minutes per day and read an estimated 1,168,000 words per year.

Students in the 50th percentile in reading read 12.9 minutes per day and read an estimated 601,000 words per year.

Finally, those students in the 10th percentile read 1.6 minutes per day and an estimated 51,000 words per year.

The National Endowment for the Arts conducted a similar study of 12th graders and found very similar results. Those who read almost every day scored higher in reading and writing than those who read once or twice a week or once or twice a month.

I’m not one who spends a lot of time with numbers. In fact, I’m a bit math-phobic, but looking at a difference of almost 4 million words read per year between top readers and average readers floored me. It reinforced my rationale for providing my students independent reading time each day.

It also made me really proud of my students.

They do read. They’re excited about reading. We have amazing and rich conversations about text. As of February 15 my 96 middle schoolers read approximately 1800 books this school year. The best part of my school day is when I can talk to kids about what they’re reading. They have tools to express their disinterest in something we’re reading a class because they will contrast what they don’t like with what they do like to read. As one of my seventh graders said the other day as we discussed Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry by Mildred D. Taylor, “The last two chapters totally made up for the whole rest of the book. They actually saved the book for me. I didn’t like it, but I was glad I stuck with it because those chapters were great!” That comment lead to a discussion about what the reader likes to read (self-awareness) and an appreciation about the structure of Taylor’s novel. The child was able to understand why there was so much description in the beginning of the novel. He said that he wouldn’t have enjoyed the ending as much if he didn’t know the characters the way he did. From this one comment, I knew the student had developed reading stamina (this was not a child who would have stuck with this text in September) and the ability to evaluate text . Reflecting on his comment, my hypothesis is that there are a combination of forces at work here, one of which is independent reading.

If you haven’t had a chance to read Readicide by Gallagher, I highly recommend it.

Until next time…See YA!

Anderson, R.C., Wilson, P.T., and Fielding, L.G. (1988). Growth in reading and how children spend their time outside of school. Reading Research Quarterly, 23(3). 285- 303.

Gallagher, K. (2009). Readicide: How schools are killing reading and what you can do about it. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.