I recently sat with some department colleagues discussing curriculum. The conversation turned to teaching shared texts and requiring independent novels. I was surprised to hear my colleagues struggled to get students to read a choice book at the same time a shared text (whole-class novel or lit circles) was being read. They were surprised to hear that my students read both. My colleagues said there was no way their kids would do both. I replied, “But mine do, so what am I doing differently?” My students were no more the avid reader than theirs. They weren’t any brighter or any more in love with ELA than theirs. We sat around a group of desks pondering that question, and no one had an answer. We threw some ideas around but really came up short.

However, that conversation has haunted me. I don’t believe I’m doing anything differently than my colleagues. We’re a strong grade-level department. Walk into any of our classrooms at any time and our kids are actively engaged reading, writing, discussing, presenting, listening—in a sense “doing English language arts.” They move to the next grade with a strong foundation (I know because I teach both grades). So why are my kids willingly (or at least giving me the appearance of willingly) reading a choice book along with assigned books? I don’t know, but I might have come closer to an answer.

“Students are likely to arrive in English class with their own assumptions about YA lit that we’ll need to disrupt” (Buehler, 2016, p. 28).

What if YA lit was changed to reading?

Students are likely to arrive in language arts literacy with their own assumptions about reading that we’ll need to disrupt.

Thinking back to the earlier conversation with my colleagues makes me think about whether I am disrupting the students’ thoughts about reading for school. Going back to reading In the Middle by Nancie Atwell some 25 years ago, I know that I am trying to disrupt reading for school. Readicide by Kelly Gallagher, Naked Reading by Teri Lesesne Book Love by Penny Kittle and countless sessions at NCTE have simply added to my need to disrupt my students’ assumptions about school reading.

First, I had to think about what I thought their assumptions were. This wasn’t hard. I just thought back to how I felt about reading for school. Then I thought about our practices as ELA teachers. Finally, I talked to my students. This is the basic list of student assumptions about school reading:

• Reading for school is always assigned.

• Even “choice” reading is assigned—students have to pick from a list of books or a specific genre or some other teacher created category

• Assigned reading is boring/stupid/worthless.

• Assigned reading, even if it’s something I might have picked up on my own, makes me not want to read it.

• Assigned reading always has an assignment with it.

• Reading logs are the worst! (Even readers hate the logs. If you want a rich conversation about reading, ask your students about reading logs and then sit back and really LISTEN. Your quietest student will even speak up about this.)

• Reading done for school is inauthentic.

So knowing these assumptions, it becomes my job to disrupt these assumptions. How have I done this:

• Book talks—lots and lots of book talks about lots and lots of genres

This means I read a lot of YA lit. Some I like. Some I don’t. Some genres I would never read, but my kids do, so I read it. Even if I don’t like a book, I know someone will. I also know they trust me (more about that in a minute), so I’m careful in my book talk. If it’s a book I’m not crazy about, I might read a passage. I might give a plot summary, and if a student asks how I liked it, my response is that I am not the target audience. They usually laugh about that. If I struggled getting into a book and then loved it, I tell them. For example, Challenger Deep was a tough 40-50 pages. However, it is totally worth it. That is part of my book talk.

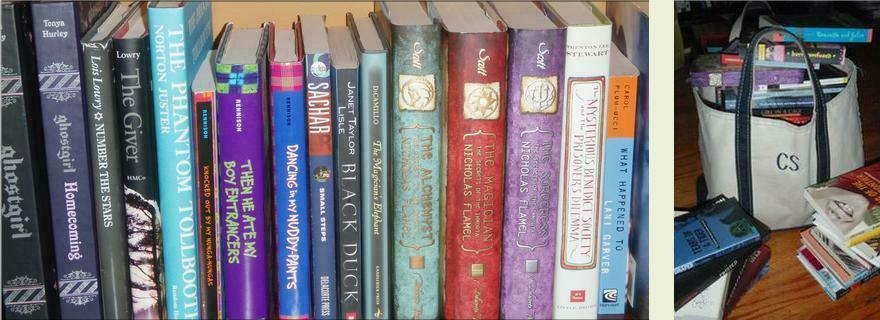

• Book speed dating—I pull books that I think kids will like and they rotate through the books, writing down titles in their tbr. At the end, they can go home with a book they were interested in. Sometimes I pull by theme. Sometimes I pull by genre. Sometimes I just pull titles. It really depends on time of the year and my kids. This is a great way to get older titles into kids hands. Son of the Mob by Gordon Korman had been languishing on my shelves, and honestly, this is one of my favorites. It gained new life through speed dating.

• Read the books–I had a children’s lit professor in college who told us that we couldn’t recommend books to kids if we didn’t know what was in them. True. Plus, I’m in ELA teacher. I became an English major so long ago because I like to read. I can polish off a YA title in a summer afternoon. Two if the book is really long. During the summer, I’ll create a shelf-talker for the book so when I book talk the book during the school year, I remember what I liked about it when I read it. I read everything I put in my class library.

• Book recommendations—My class library is pretty extensive. I’ve had a lot of years to cultivate the library. Students donate books to the library. Half.com, library book sales, and trips to the book store also add to my collection. When a student asks for a recommendation, I ask them what was the last book they loved reading. They’ll give me a title (hopefully), and I’ll follow up by asking what they liked about it. This points me in the right direction. Was it genre? Plot? Character? Then I’ll pull three titles that I think they might like. I tell them to read the back of the book, read the first page, take some time with the book. If nothing grabs them, let me know, and we’ll start again. These book recommendations are really important. You only get one first chance for a kid to trust your recommendation. Usually, I get it right, and then kids continue to ask for my recommendations. A lot of times I find kids don’t know what to read that’s good. They really have no idea. It’s like taking someone who only eats chicken fingers and grilled cheese to a fine dining establishment. There’s stuff they’ll eat, but the menu makes the choices all so overwhelming.

• Talk about reading—I tell them what I struggle with, what I like, what I don’t like. I think they think teachers have all the answers and love all the books (or only love the “boring” books). Talking about reading habits and struggles makes my reading life visible to them. I become a real person.

• Time to read—we read. Every day. No exceptions. This is the one thing that doesn’t get cut. It sends the message that reading is important to me. It should be important to them.

• Journals—we work on reading skills and literary skills through our journals. This might be before we start silent reading. It might be after. We practice the skills that make us better readers. All of us. I write too. I make my journal entries visible to them.

• Reading goals—they set a goal for each trimester. Penny Kittle does a great job explaining this in Book Love. We revisit the goal during the trimester and talk about ways to meet the goal and celebrate when they finally do meet their goal. Everyone’s goal is individual. No one’s goal is ever belittled. Most of my students only read (barely) the assigned reading the previous year. So if their goal is two books in one trimester, that’s two more books than the previous year. The following trimester, I’ll coach them on their goal. The only logs they keep are finished books and books they want to read. I keep track of their page numbers and reading via status of the class (See Atwell,In the Middle).

All of this is with their choice books. They can read whatever they want. I don’t judge. I will coach if they are reading something below where I think they should be. However, we all take breaks in our reading life. I don’t have a steady diet of heavy academic texts, despite the fact that my reading level would dictate that. So if Diary of a Wimpy Kid shows up or 39 Clues, they show up. Not making a big deal out of it helps. The student reads it and goes back to something that bit more appropriate for their skill as a reader. It’s middle school. Sometimes these books show up to see what the teacher’s reaction is going to be. No reaction is not really fun for them.

Obviously, reading shared texts looks different than this. However, I think that disrupting one part of school reading helps. This aspect of my classroom makes reading authentic. It clears the way for us to do the heavy lifting of a reader, whether it’s with choice books or a shared reading experience.

I recently talked with an eighth grader who came in to grab a book from my class library. I noted that she had just taken out the book she was returning (seriously, she took it out the day before). She said, “Well, when I’ve finished everything I have to do I just want to read.” I asked her if she would have said this at the beginning of the school year or even last year, and she said, “No. But I’ve found some really good books. They’re so much better than television.”

And that’s what happens when school reading is disrupted, I guess.