Because I’ve been reading a lot about classroom libraries, I’ve been making a conscious effort to add books to my room that represent all of my students. I’ll be honest, teaching in a predominantly white, middle/upper-middle class school, I wasn’t sure how students would respond, but not all of my students were white, upper-middle class, Christian, heterosexual people. Not all of my students had families that were “normal.” And so, I started listening more closely to students talk about books like Out of My Mind by Sharon Draper, Rules by Cynthia Lord , or Wonder by RJ Palacio. I began to have conversations with my students when I thought about adding a book like Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the UniverseBenjamin and Aristotle Discover the Secrets of the Universe by Benjamin Alire Saenz to the class library. I took their suggestions when they recommended books to me. I asked them about favorite characters, especially when the books they were reading had characters who were no cis-gendered, mainstream people.

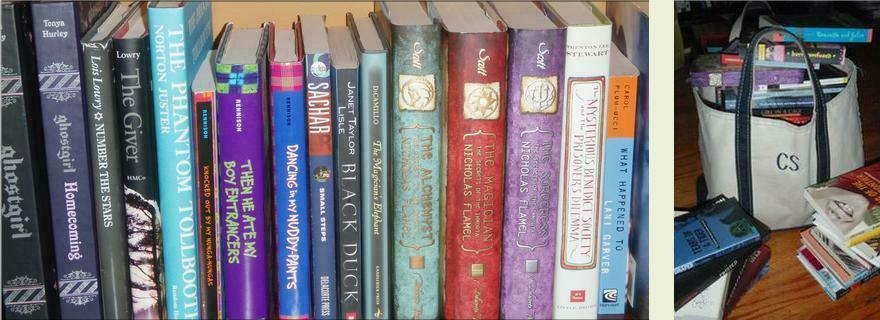

This past year, I was able to add a lot of books that not only qualified as diverse books–books with protagonists of color, protagonists who were differently able, or books by authors of color–but I was able to add books that focused on current issues–books such as The Hate U Give, The Sun Is Also a Star, and All We Have Left.

Today, I just finished You Bring the Distant Near by Mitali Perkins. I cannot wait for this book to come out September 12 and put it in my classroom library.

In 15 days, I start back to school. In 20 days, a new group of seventh-grade students and a returning group of eighth graders will arrive in my room. I think about the divide in our country and how it seems to grow instead of shrink. I think about the ways that literacy can work to bridge that gap.

I first learned of Mitali Perkins through an article in the School Library Journal titled “Straight Talk on Race: Challenging the Stereotypes in Kids’ Books” Perkins talks about the gap between her world in her traditional Bengali home and her world in school with her suburban Californian peers. She talks about the ways the gap felt large and small. And as I read, I thought about my role as a teacher in a suburban middle school. How do I help close the gaps that might exist between students’ homes and white culture in school?

Perkins goes on to say, “Adult silence about an issue sends a powerful message to young people.” She cites a 2000 essay by Jeanne Copenhaver stating, “‘The social stigma attached to candid discussions of racial themes creates a silence preventing explicit talk about race, and this silence leads to further, subtle segregation—even within multiethnic, otherwise harmonious classrooms.’” Not talking about race simply adds to the problem at hand. Perkins gives readers five questions to think about and talk about when discussing and sharing books.

And while all of these things were thought-provoking for me, what really spoke to me was that she discusses these questions in relation to books she’s written. She even provides an example from The Sunita Experiment (first published in 1993). Called out by a reviewer for “unnecessary exoticization” of the protagonist, Perkins goes back and looks critically at her words. In 2005 she had the opportunity to revise the book.

In her newest book, Perkins weaves decades, cultures, and voices to tell the stories of three generations of Bengali women. I can go on and on about Perkins writing and her use of character and the shifts in voice and time. Without a doubt, I loved this book. There are so many layers to it. It’s a book I want to read with a book club and discuss the myriad of themes. It’s a book I wanted to reread as soon as I finished. It’s a book I want to teach in my grad class.

But the book is more than these things.

In the last five days, I’ve watched violence erupt as Nazis, white supremacists, and KKK members protested the removal of statue in Charlottesville. A statue that was erected long after Reconstruction. A statue that was erected in the Jim Crow South as a reminder to those who were not white (and male) that they were not in power. That they had no rights. That they had no voice.

Personally speaking, these statues never should have been erected. I understand why they were. They are powerful markers of intimidation. However, they are also memorials to people who lead a revolt against the United States. These statues do not make America great. They further divide our country. The fact that the president refuses to denounce the violence perpetrated by these hate groups, that the president feels it’s okay these statues remain, that the president says that there “very nice people” within the hate groups, that the president blames the violence on those seeking to push back the “protesters” and protect those in the “protesters’” way (knowing these groups “protesting” came to Charlottesville to enact violence on others), and that the president continues to try to change the narrative about the things that do make America a great country disturbs me. Reflecting on Ranee, Sonia, Tara, Anu, and Shanti, three generation of strong women in You Bring the Distant Near, reminds me of what does make America great. They are the story of late 20th Century immigration. They are the story of a global village.

Towards the end of the novel, the attack on the World Trade Towers on 9/11 have a strong affect on Ranee. “‘Why are Americans so stupid? So trusting? They let anybody in this country! Even people who hate them!’”

“‘I know, Didu,’ Shanti answers. ‘But that’s what makes us great–the statue isn’t going to put her torch down, not even after this’” (Perkins 156).

On the base of the Statue of Liberty is Emma Lazarus’ poem “The New Colosuss” most of us know only the final lines of the poem: “Give me your tired, your poor…” However, the poem begins by painting a clear image of the lady in the harbor, a sight I take for granted since I grew up practically in her shadow.

“Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

‘Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!’ cries she

With silent lips. ‘Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!’

The poem’s tone is soothing and comforting. You are hurting, you are lost, you are without a home, but I will help you.

A poem by Rabindranath Tagore gives Perkins’ novel its name. It is not a poem I was familar with, but luckily, the Poetry Foundation had the poem. Reading the first stanza,

“thou hast made me known to friends whom I knew not. Thou hast given me seats in homes not my own. Thou hast brought the distant near and made a brother of the stranger. I am uneasy at heart when I have to leave my accustomed shelter; I forgot that there abides the old in the new, and that there also thou abidest” (Poems, Rabindranath Tagore)

I’m struck by how similar both poems are–I didn’t know you, but you welcomed me, you gave me shelter, and you became family.

As I get ready to head back to school, I will continue to think about how I talk about race in my classroom, what my library reflects back to my students, and how I continue to welcome all and make “the distant near.”